When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, they directed their tyrrany at the Jewish people, who were imprisoned in ghettos and murdered by the millions.

The Nazis hoped Adolf Hitler’s systematic dehumanization and routine murder of Jews would remain hidden from the rest of the world

They tried to hide the traces of their horrific activities so that no one would know what really happened in the concentration camps.

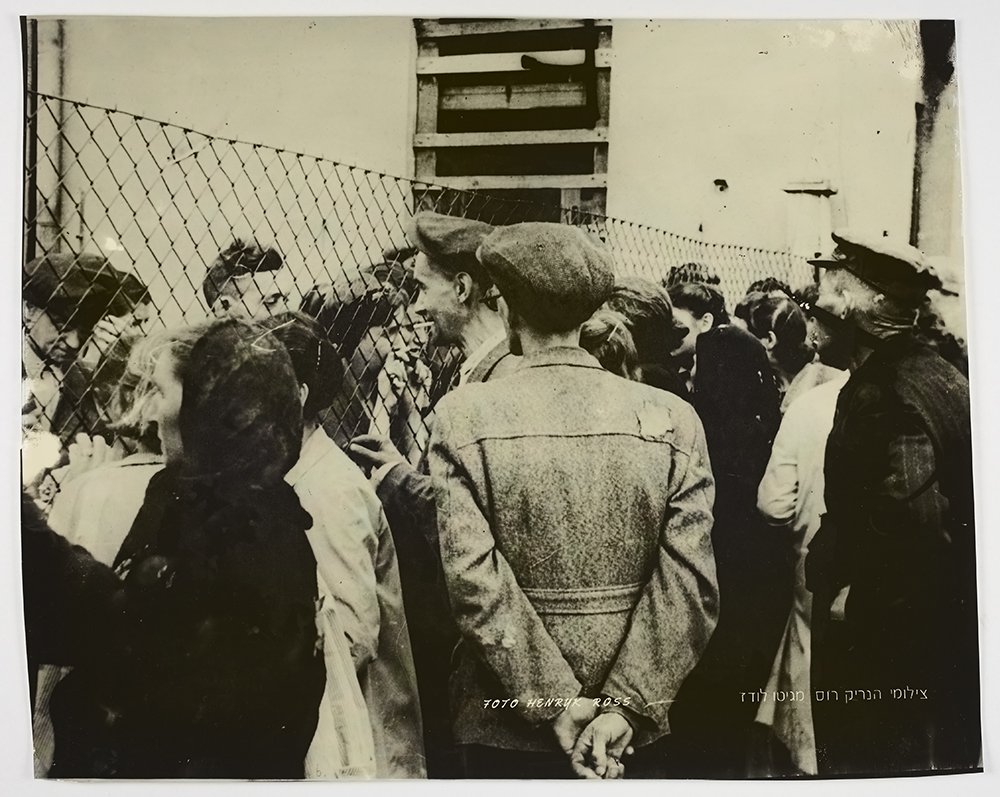

But the photographer Henryk Ross refused to let the Holocaust go unnoticed.

He secretly documented the genocide — even though he risked his life by taking his pictures.

Henryk Ross buried about 6,000 negatives in a field and when the war was over, he returned to dig up the painful truth that he had captured; that the Nazis had imprisoned thousands of Jews, who lived and died in terrible conditions.

Most people were horrified by the pictures, but many people were also grateful that Henryk dared take them — because they show a part of our history that we can never forget.

Here are his powerful photographs:

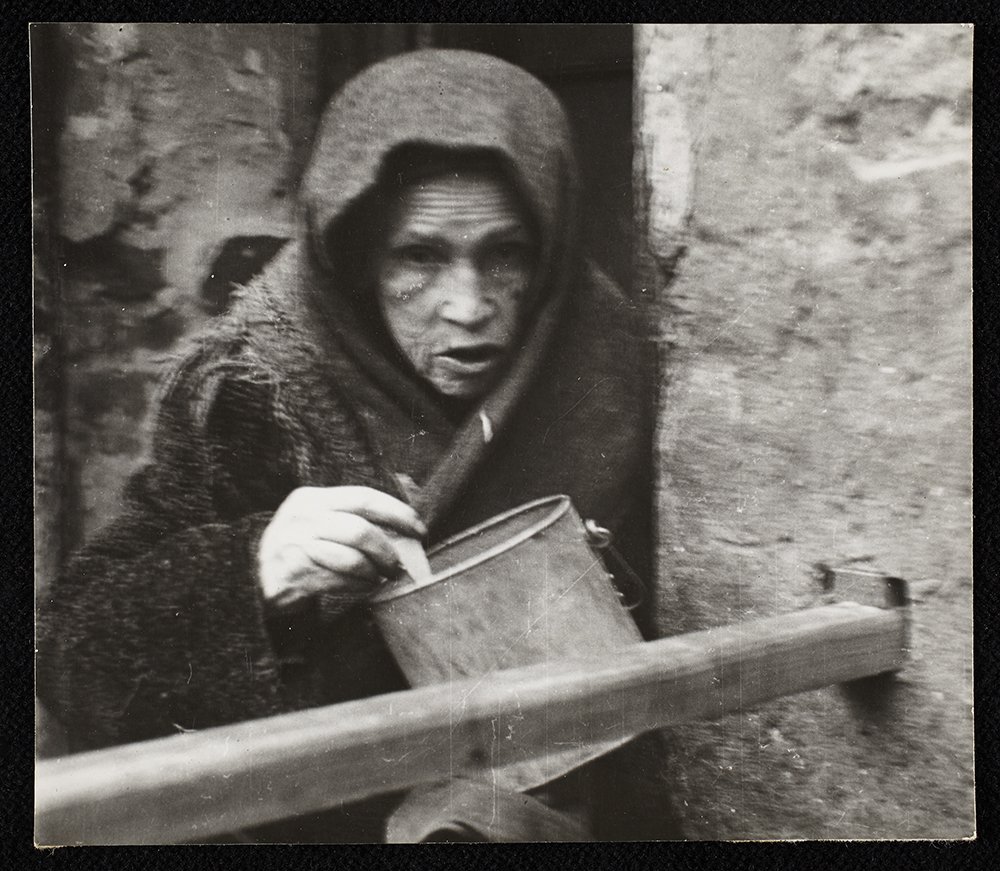

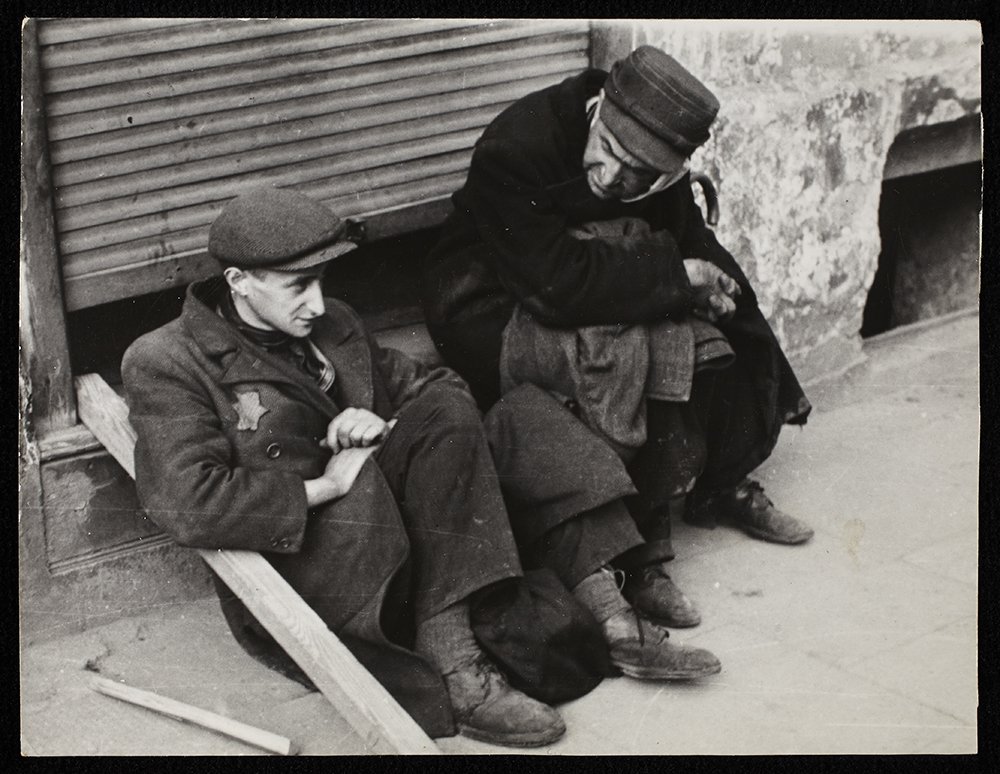

Ross’ photos, which were shown at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Canada, show the awful reality of the Lodz ghetto, where Ross and his family were detained for four years together along with more than 160,000 Polish Jews.

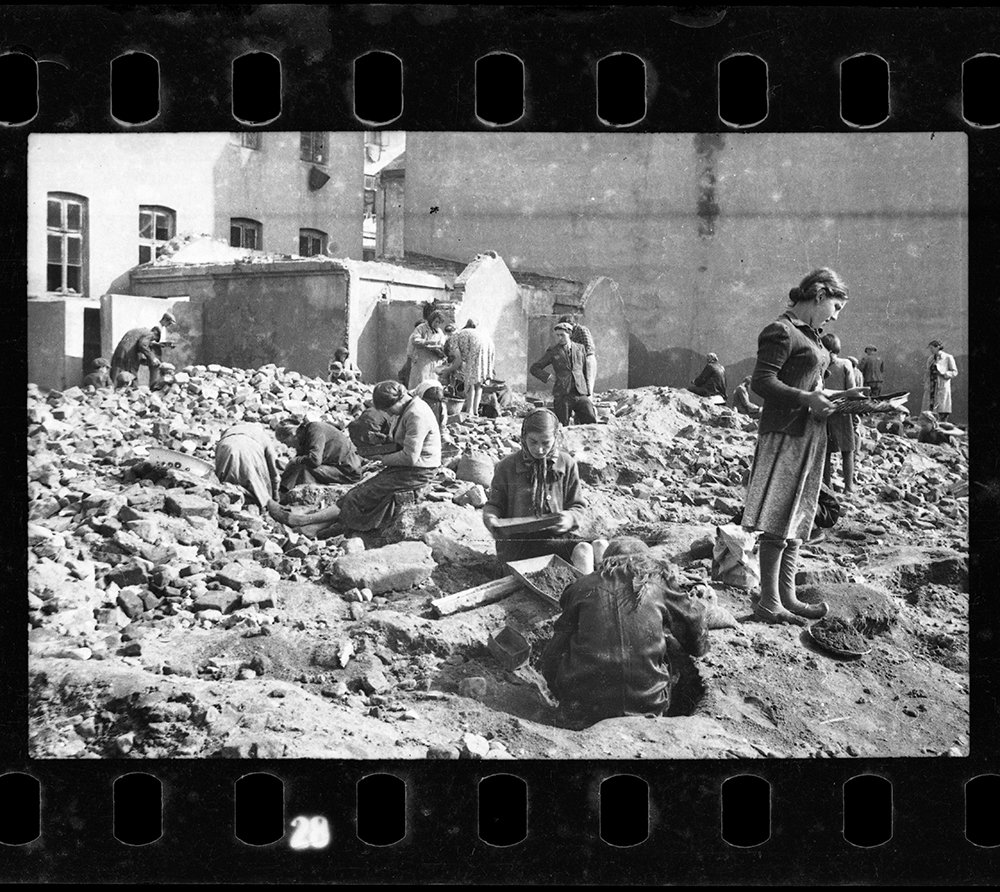

Among the photographs, many show the nasty truth of the genocide of the Jewish people. Bodies are stacked high and anxious children search for food in the dirt in some pictures, while others capture the incredible resilience of those trapped in the grip of Nazi terror.

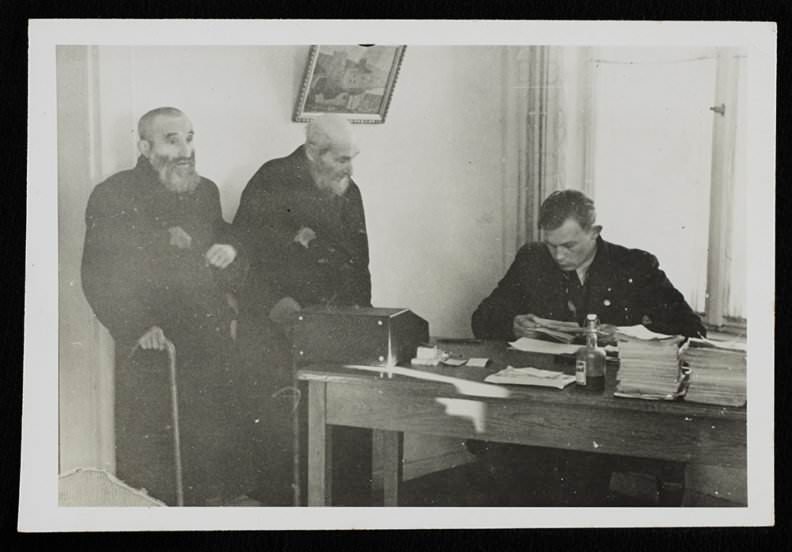

Warsaw-born Henryk Ross worked as a sports photographer before the war, and after the Lodz ghetto was created, he was “assigned” to take identification pictures and propaganda photos at the ghetto’s factories.

But the role served as perfect cover for Ross, who secretly took many pictures of ghetto life.

Before he died in 1991, Ross revealed how and why he saved his photos.

“I buried my negatives in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy… I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry. I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom.”

When Ross wasn’t working on behalf of the Nazi regime, he took photos through holes in walls, through the folds of his jacket, and on back streets when no one was looking.

Ross risked his life and those of his family by taking the photographs.

Ross explained, “Having an official camera, I was able to capture all the tragic period in the Lodz Ghetto. I did it knowing that if I were caught my family and I would be tortured and killed.”

The conditions in the ghetto were terrible; large areas had neither running water nor sewage systems.

More than 20 percent of residents died due to poor living conditions.

Ghettos like Lodz made it easier for the Nazi regime to control Jews, take their property, and force them into labor.

German Jews were sent to ghettos in occupied Poland, Latvia, and Lithuania, and Roma people arrested in Austria were sent to ghettos to the east.

The Lodz ghetto was divided into three parts and was surrounded by barbed wire fences and walls.

After the liberation of Lodz, Ross dug up his box of negatives and recovered his archive.

Now, the grainy, black and white pictures serve as a reminder of what can actually happen when we don’t protect the rights of all people.

Ross said about the picture above, “There was a burial society. To begin with, they were taking for burial two or three victims of starvation. But afterward, when the number reached 120, it became necessary to construct special carts to transport bodies. I saw entire families, skeletons of people, who were dying with their children.”

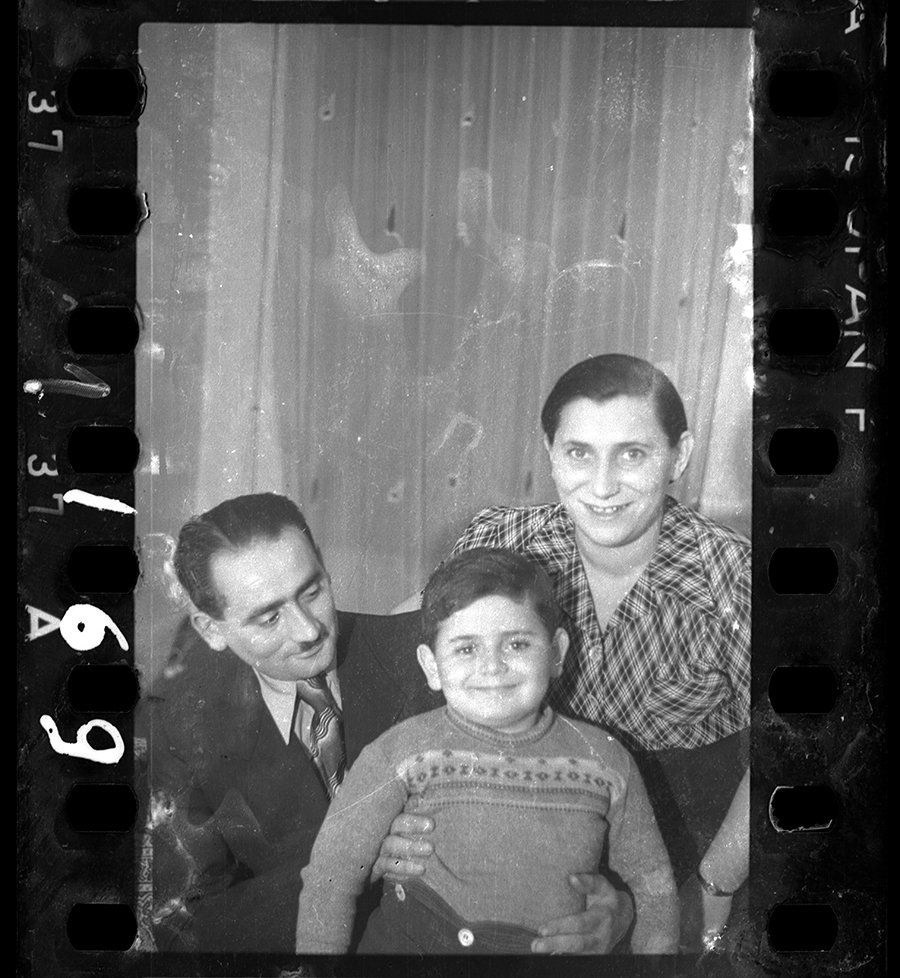

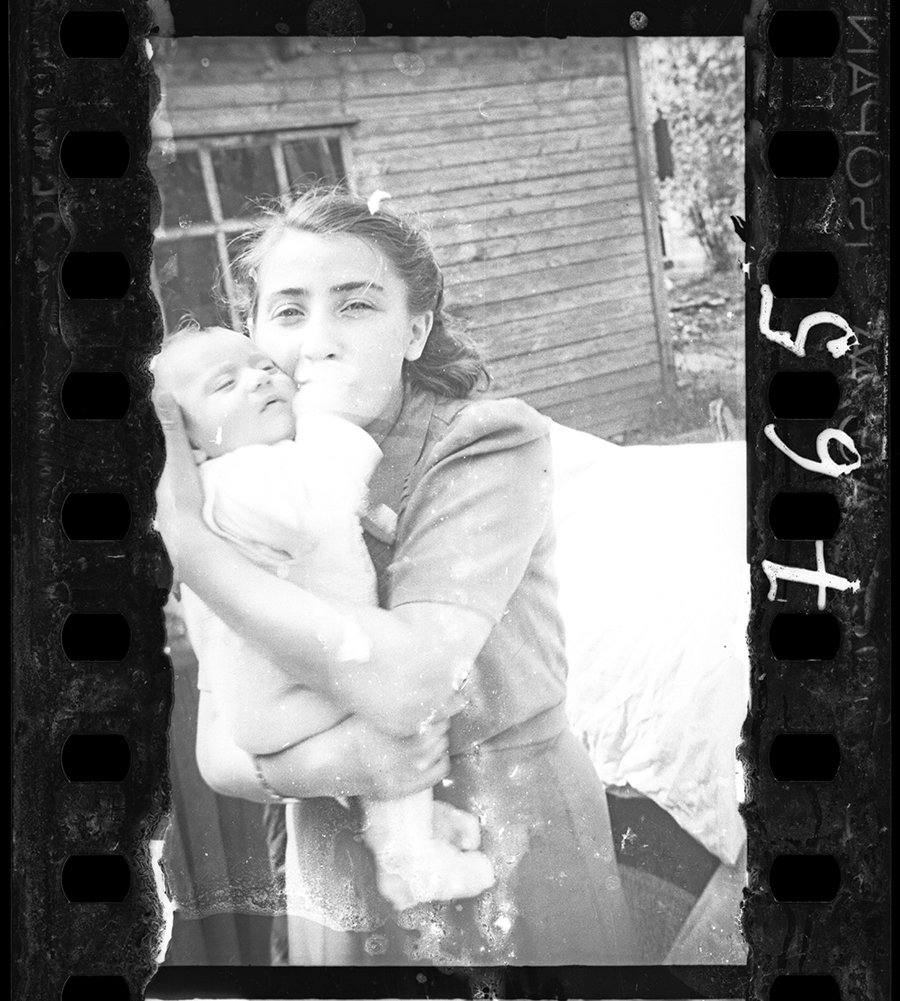

But besides all the tragic things that can be seen in the pictures, they also carry a message of human strength and hope. Because among all of the pictures are thousands of photographs of families celebrating births, marriages, and the other little moments of happiness that occasionally happened in the ghetto.

According to the gallery, “The Henryk Ross Lodz Ghetto Collection is a unique compilation of approximately 3,000 35 mm cellulose nitrate negatives, vintage prints, graphic art, posters, and personal ephemera. They are testimony of the potential for art to be both an act of resistance and remembrance.”

When the Lodz ghetto was closed, Ross buried his collection of negatives in an iron-lined box.

When he dug up the collection in March 1945, Ross discovered that many of the negatives had been severely damaged by water.

The swirls and trails you see in some of these pictures are a result of this.

In January 1945, the Red Army approached Lodz to liberate its prisoners. But not many were still alive and lving in the ghetto.

In August of the year before, most of the ghetto’s remaining residents were sent to Auschwitz.

The ones who were still there had gone into hiding.

When the Red Army liberated Lodz on January 19, 1945, there were only 877 people in the camp.

Henryk Ross and his wife, Stefania, were among them.

They were married in the ghetto, like many other young couples.

These brave people refused to be crushed by the racist regime.

Instead, they supported each other and shared moments of happiness together, something that Ross managed to capture in his photographs.

Henryk Ross’ entire collection was donated the Art Gallery of Ontario by the Archive of Modern Conflict in 2007.

Although Ross’s photos show the most extreme cruelty and human suffering, there is always a dignity in those who are photographed.

Like in this photo of two girls, who are probably best friends.

Immediately after the Germans took Lodz, most of the Jewish residents’ financial assets were confiscated.

Jewish people couldn’t own cars or radios and weren’t allowed to travel on public transport.

Lodz has a particularly remarkable history, as it was isolated from the rest of the world and near Chelmno, the first center set up to gas Jewish people.

Only about 10,000 of the people who entered Lodz survived the war.

Before the war, Lodz was known for its textile industry, and its residents tried to use their work ethic to their advantage in their struggle for survival.

That work ethic also characterized Ross, who was forced to take propaganda photographs.

Although a significant amount of Ross’ secret photos were damaged, almost 3,000 negatives survived.

Today, they represent the most widely known collection of documentation of the Holocaust and the ghettos — all taken by a single Jewish photographer.

It’s a haunting record of one of the worst crimes in human history.

Adolf Hitler and the Nazis didn’t want us to see what they were doing.

They didn’t want to show off the cruel, systematic eradication of millions of people.

But Henryk Ross worked hard to make sure the truth got out.

Henryk Ross’s important photographs show that we can never let this happen again.

And it’s also a tribute to the power of humans when they have nothing but each other.

Please share this story so that everyone you know can see these powerful photographs!

Published by Newsner, please like