It’s chilling to remember that even the world’s most notorious killers — dictators, mass murderers, serial predators — were once innocent children.

The boy we’re about to focus on would grow up to become one of California’s most feared killers, believed to have taken the lives of 51 young boys.

From 1971 to 1983, he struck fear into an entire state, and even decades later, the memories of his horrifying crimes remain deeply etched in the minds of those who lived through the terror and those forever connect

Born on March 19, 1945, in Long Beach, California, this boy was the only son in a modest, working-class family that had moved west from Wyoming in search of stability and sunshine.

From the outside, it all seemed appeared ordinary, a family chasing the American dream in the new suburbs of postwar Southern California.

But inside that small, pale-blue house, a strange quietness always lingered.

Growing up, the boy was an intelligent, observant child. He was polite, reserved, almost painfully meticulous. He loved puzzles, math, and order. His teachers described him as bright and obedient. His mother, Opal, doted on him; his father, Harold, worked long hours at a factory and expected discipline.

Neighbors would later recall how neat his room was, how his toys were always arranged just so.

Even as a boy, he sought control, a trait that would grow darker with time.

A model student

When the family moved to the growing suburb of Westminster in Orange County, the young man fit right in with the conservative climate of the 1950s. In high school, classmates remembered him as “smart, clean-cut, and quiet.”

He excelled academically and was described as “somewhere right of Attila the Hun” politically, a fervent supporter of traditional values, of the military, and of order.

He joined student government, joined the debate team, and seemed destined for a respectable life. After graduating in 1963, he enrolled at Claremont Men’s College, majoring in economics. He threw himself into campus politics, campaigning for Barry Goldwater and supporting the Vietnam War.

But by his junior year, something began to shift.

He grew a beard. His politics softened. He started attending anti-war rallies and, quietly, began coming to terms with a part of himself he had long suppressed.

By 1969, he had come out as gay, a revelation that shocked his family and cost him his position in the Air Force Reserve, where he had been serving as a trainee. Officially, he was discharged for “medical reasons.”

Unofficially, it was for being homosexual.

The drift begins

After leaving the service, he stayed in Southern California, working odd jobs — bartender, computer programmer, waiter.

He was articulate, well-dressed, and always courteous. To acquaintances, he was a mild, urbane young man with an IQ of 129 and a love for conversation.

But behind that calm exterior, something was twisting.

He began using drugs, mostly amphetamines and barbiturates. He also developed a taste for alcohol. His friends noticed erratic behavior: days of isolation, bursts of anger, long absences with no explanation.

The coastal nightlife of Long Beach and Sunset Beach was booming, and the young man found himself drawn to its energy, to the gay bars that became havens for those still living in secrecy. He worked at one called The Stables, serving drinks and chatting easily with regulars.

But he was also prowling. Watching. Testing limits.

The first victim

In March 1970, a frightened, disoriented 13-year-old runaway named Joseph Fancher stumbled barefoot into a Long Beach bar, trembling and incoherent. Police soon learned he had been drugged and assaulted by an older man who had offered him a place to stay.

olice eventually got a name for the suspect, and when officers searched his apartment, they discovered the boy’s shoes along with a cabinet full of sedatives and prescription pills. But since they had entered without a warrant, the evidence was thrown out, and the man walked free.

No one knew it at the time, but the Fancher incident would become the first in a string of horrors that would stretch over more than a decade.

Bodies by the highway

Over the next several years, a grim pattern began to emerge across Southern California. Young men, mostly in their teens or early twenties, often Marines or hitchhikers, began vanishing.

Their bodies would later be found along highways, ravines, and remote fields.

The killings were brutal. The victims were drugged, restrained, and killed with quiet precision. Many bore signs of torture. Investigators from Orange County, Los Angeles, and San Bernardino realized they were dealing with a single predator, a man who seemed to roam the freeway system like a phantom.

By 1975, police had linked several of the cases but had no suspect.

They didn’t yet know the killer was living comfortably in Long Beach, working as a computer programmer, and spending his weekends hunting for victims.

For years, he managed to stay one step ahead of the law, even as the bodies kept turning up. Between 1971 and 1983, he kidnapped, tortured, and murdered at least sixteen men and boys.

A twist of fate

Then, on a warm spring night in May 1983, fate intervened.

At around 1:00 a.m., two California Highway Patrol officers pulled over a Toyota Celica on the 405 Freeway near Mission Viejo. The driver appeared intoxicated. A half-empty beer bottle sat beside him.

When one officer looked toward the passenger seat, he froze.

There, slumped lifelessly against the window, was the body of a young Marine named Terry Gambrel. His belt was around his neck.

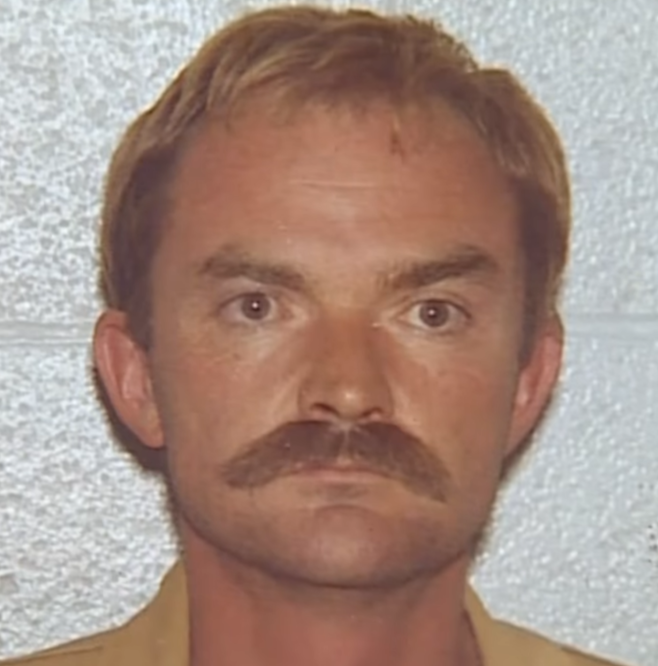

The driver’s license revealed a name that would soon become infamous: Randy Kraft. The press would later dub him “The Scorecard Killer.”

Inside the car, officers found a briefcase containing drugs, alcohol, and a notebook.

At his home, investigators uncovered a disturbing collection — photographs, victims’ personal belongings, and evidence linking him to a trail of murders stretching from California to Oregon. But the most chilling find was a neatly written list: more than sixty cryptic entries, each one a clue.

Every line represented a victim

The short, coded phrases, “Stable,” “Marine Drum,” “Iowa,” “Parking Lot”, seemed meaningless at first. But detectives soon realized what they were looking at: a scorecard of death. Every line, they believed, represented a victim.

One entry, “Stable,” appeared to reference the bar where Kraft once worked. Another, “Airplane Hill,” matched the location where a body had been discovered near an airfield. The list spanned more than a decade — a meticulous record of horror.

He documented everything, as though each life taken was a statistic, each murder another act of control.

All of his victims were young white men, mostly in their late teens or early twenties — many found with drugs or alcohol in their.

Kraft’s method rarely changed: he’d pick up his victims, offer them drinks laced with sedatives, and once they were unconscious, commit unspeakable acts. Many were found unclothed, their bodies showing signs of methodical torture.

Then came the photographs.

Victims posed with eerie precision, some appearing to sleep, others unmistakably lifeless. The Polaroids, found in his possession, would become some of the most haunting pieces of evidence in the case.

Randy Steven Kraft’s stunned his friends and co-workers. One of his closest friends recalled him as “a normal kid, just like everybody else.” To the outside world, he was a loyal friend, a devoted family member, and a talented computer expert.

“Everybody liked Randy,” said Kay Frazell, a former classmate who said she once had a crush on him, to LA Times.

Trial and reactions

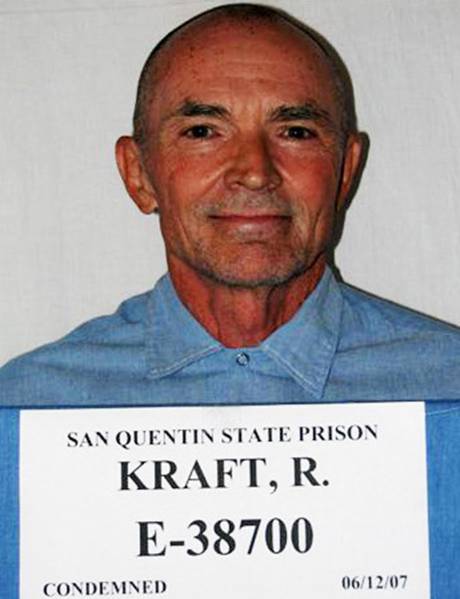

In 1989, following one of the longest and most expensive trials in Orange County history, Randy Steven Kraft was convicted of sixteen murders, as well as multiple counts of sodomy and torture.

In his defense, Kraft offered only a single statement:

“I have not murdered anyone. I believe any reasonable review of the record will show that,” he said before calmly sitting down and pouring himself a glass of water.

When the judge read the verdict, death, Kraft sat motionless, showing no emotion.

He was sent to San Quentin’s death row.

Several relatives of Kraft’s victims let out sighs of relief as the sentence was handed down. Some wept, others smiled. One grieving father shouted, “Burn in hell, Kraft. Burn in hell,” as the convicted killer was led out of the courtroom.

”Even after he’s executed, the anger is still going to be there” said Rodger DeVaul Sr, the father of victim Rodger James DeVaul, 20, at the time.

The sensational news of Kraft’s arrest sent his family into hiding from the press. They were ordinary, private people suddenly thrust into a nightmare of headlines and flashing cameras.

“It has been devastating for them,” said Kraft’s attorney, C. Thomas McDonald, in 1989.

“But they love Randy, and they have been very devoted to him since his arrest.”

“Looked like everyone else”

In over forty years behind bars, he has never admitted to a single killing.

Detectives still believe there are dozens more victims who will never be identified.

In 2012, retired homicide detective Dan Salcedo came face-to-face with Kraft inside San Quentin.

“It’s weird — when you look at him, there’s nothing memorable,” Salcedo told Police1. “He’s not the prototypical media version of what a killer looks like. If you put him in a room filled with people, he’s the last one you’d pick.”

Salcedo had hoped for a confession, or at least a clue about the cases still haunting California’s files. But Kraft said nothing.

“When I looked into his eyes,” Salcedo recalled, “I felt nothing. No aura of evil. Just a bitter old man.”

When the interview ended, Kraft quietly called for the guard and was led away.

Death sentence upheld

To Salcedo, Kraft represented the purest form of “quiet evil.”

“The banality of evil,” he later called it. “He looked like a neighbor, a coworker. Nothing about him screamed danger. And maybe that’s the most terrifying part.”

Even today, investigators revisit unsolved murders, searching for ties to the mysterious entries on Kraft’s list. Some families have finally found answers through DNA testing; others are still waiting for closure that may never come.

Kraft now spends his days confined to a small cell aging, silent, unrepentant. A man who once kept everything in order, except his soul.

His conviction and death sentence were upheld by the California Supreme Court on August 9, 2000. As of 2025, he remains on death row at the California Institution for Men in San Bernardino County, still denying any involvement in the murders for which he was convicted, or the many others he’s suspected of committing.

READ MORE

- LA Dodgers star confirms baby daughter has died in heartbreaking post

- ‘Dynasty’ & ‘The Paper Chase’ star dies at 98